In the the last post I talked about some high-level ideas about writing a Database in Go. I only touched on the outline of the project. In this post, I am going to focus on the first part of my implementation, the key-value in-memory database. We will see how to implement it, some performance numbers and what’s next.

First Some High-Level Background

One of the must-have features of any frequently accessed database in today’s time is fast access to the stored data. Data access performance is dependent on whether data is stored in the main memory or on disk. Different databases use different strategies for storing the data based on what kind of application they cater for. Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of databases, DB’s that keep all the data on transient storage(RAM) and the DB’s that store data in permanent storage(hard disks) and loads it in memory. The majority of the databases, some way or other, either use a combination of both or can be configured to use both.

In-memory DBs use main memory for storage, which allows for fast access of data without the overhead of time spent in seeking and accessing the data on disk but at the cost of data loss in case of power failure or some other crash. Also, there is only a limited amount of memory(a fraction of disk size) available on a system.

Majority of relational and non-relational DBs use disks for storing the data. But indices and any frequently accessed data are stored in the main memory for fast access. On-disk storage makes the data persistent and has a virtually unlimited amount of storage available but at the cost of a much slower access time.

Let’s take an example of two famous databases, MySQL and Redis storage strategy before coming to the performance. Both store data but have completely different applications and are used for very different kinds of access patterns.

Mysql: stores data on the disk in flat files. All the data is stored in flat files(under /var/lib/mysql/ by default). On-disk data is the source of truth and in case of a failure, DB recovers successfully with the latest committed data. It offers a very strong consistency guarantee. But MySQL also uses main memory. It caches data in the main memory for fast random data access. It uses linked lists and LRU caching strategy for caching and invalidating the data. MySQL uses a data structure called B-Tree(or B+tree or hashmap) for keeping a memory map of indexed keys that point to actual data on disk.

Redis: is a fast in-memory database Mostly used as a fast cache. Like MySQL Redis also is a hybrid version of the two classes of DBs. But unlike MySQL, It uses main-memory as primary storage but it is persistent using disk storage. Redis is fast but has a limitation that data can only be as large as available RAM on the system. For persistence, it uses RDB(point-in-time snapshot) or AOF(an append write-ahead log) strategy.

The above information is a very oversimplified explanation of Database and their storage. It’s a huge topic that can’t be covered in a blog like this. Check Redis technical blogs.

In-Memory Key-Value Datastore

Source code: https://github.com/amitt001/moodb

Coming back to the main topic of this post. How an in-memory key-value data store can be implemented in Go. For this project, at the time of writing this blog, I am using a hashmap for storing the key-value data.

Why Use Hash Table?

Hash table is a powerful data structure that offers an amortized O(1) time access to data. This is the data structure that the key-values DBs use. It offers a fast exact key lookup. The reason why I am not using a more sophisticated data structure like balanced trees etc because at this point my use case is to do an exact key matching to get the value. There is no range base, pattern matching, sorted queries. So hashmap works fine in this case. Later when I implement sorting and other functionality I will look into alternative implementation.

How To Implement Key-Value Store In Go?

Go has a built-in hash table data structure implementation called map. It’s signature is like this map[KeyType]ValueType.

Since, the last post I have managed to add a working key-value data store that takes 3 commands, GET, SET, and DELETE. I am using Go’s map data structure. With key as string and value as a struct.

// KVRow individual row in db

type KVRow struct {

Key string

Value string

createdAt int64

}

// KVStore DB memory map

type KVStore struct {

data map[string]KVRow

mux sync.Mutex

}

data map[string]KVRow: this is the main data structure that stores key-value. Key is stored as a string and value is a struct of key-value data. The value struct can be extended to store more info like a pointer to the next key.

In relational DB terms, KVStore will be like a table and KVRow will be individual rows in the table. Using map offers faster ~O(1) access to data.

To operate on this table we need methods that are attached to the structs. In an object-orientated language, I would have used classes and class methods for this but in Go, there are no classes. It only has structs but Go does offer methods that are defined on struct types. Let’s see how to implement a GET method:

// Get value for a key

func (s *KVStore) Get(key string) (string, error) {

if s.data[key] != (KVRow{}) {

return s.data[key].Value, nil

}

return "", ErrKeyNotFound

}

This (s *KVStore) syntax before function name tells Go that this is a struct method defined for a struct KVStore. Here s is the pointer to struct type KVStore. Get method receives this struct pointer and can access all the fields and modify it. The other two methods Set and Del are created similarly. Check the source code for implementation.

This in-memory hash table implementation provides fast access but is limited by available RAM.

I have also divided the client and the server into different processes. Client and server communicate using protobuf messages. The Client interacts with the server using gRPC protocol. But that’s not something I will discuss in this post. I am mentioning this because this has a network impact on the performance of the client.

Testing Performance

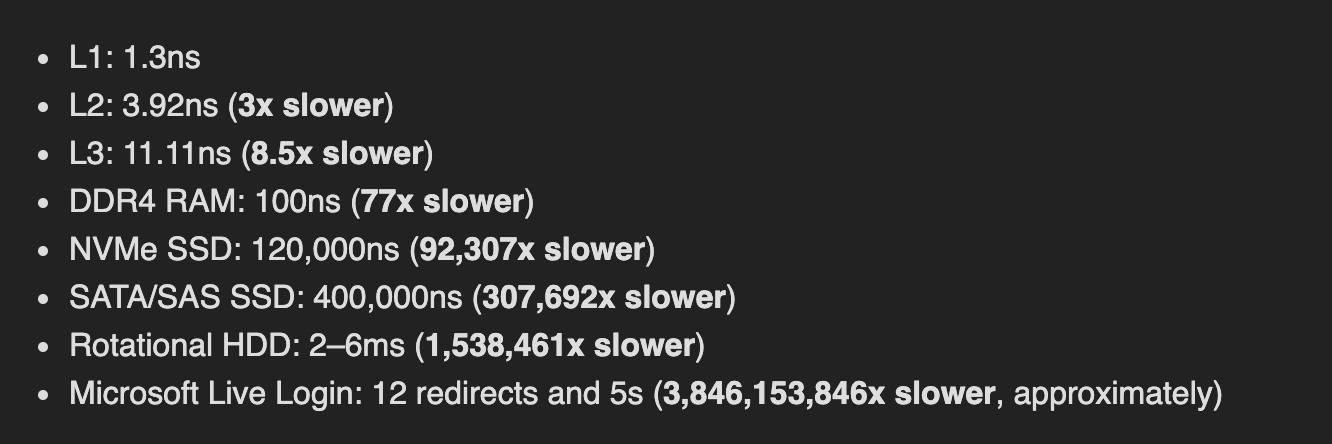

Man memory is fast disk is slow. This is a fact but how slow is a disk, 10x, 100x, 1000x? It can be as slow as ~1,00,000x! But the exact number is not important and it is always changing.

System memory: ~100ns latency - 8x 8GB

NVMe SSD: ~120μs

SATA or SAS SSD: ~400–600μs

Rotational HDD: 2–6ms

This is taken from a very informative Stack Overflow Caching blog

I ran a simple test on my DB to check its performance.

100K sequential writes

SET 119.477309ms

GET: 30.923911ms

SET(client): 21.412187772s

GET(client): 21.318625648s

As expected, the client is very slow as compared to direct hash table use. Which makes sense as 1) the client has an added delay of network calls, 2) sequential read and writes.

Let’s see if parallel writes will help. Using Goroutines

100k Parallel writes:

SET(parallel): 157.4008ms

GET(parallel): 35.448756ms

SET(client, parallel): 4.385938809s

GET(client, parallel): 3.698692113s

Much better! 5x speedup for clients.

Source code to benchmark this. This is not a bad performance. gRPC is also impressive here and easily handling ~20k requests/second. One more thing to note here is direct database access performance went down by a few ms. The reason is Goroutines context-switching overhead and direct operations on the hash table don’t have the i/o like the client so goroutinues don’t add any benefits. As the database has locks and at any given time only one process can update it. So it doesn’t get a speed bump like the HTTP client.

That’s it for now. In the next post, I will talk about WAL implementation and again run a benchmark with WAL.

Update: May 01st, 2022: I ended up implementing the first version of a simple WAL for the DB in 2020 itself but never got a chance to write a blog about it. Since it has been so long and I don’t have a plan to put the effort into this project, for now, I won’t be publishing a new blog regarding this until (if) I again work on it.